Italian art

Since ancient times, the Italian peninsula has been home to diverse civilizations: the Greeks in the south, the Etruscans in the centre, and the Celts in the north. The numerous Rock Drawings in Valcamonica date back as far as 8,000 BC. Rich artistic remains survive from the Etruscan civilization, including thousands of tombs, as well as from the Greek colonies at Paestum, Agrigento, and other sites. With the rise of Ancient Rome, Italy became the cultural and political centre of a vast empire. Roman ruins across the country are extraordinarily rich, from the grand imperial monuments of Rome to the remarkably preserved everyday architecture of Pompeii and neighbouring sites.

Following the fall of the Western Roman Empire, Italy remained an important artistic centre throughout the Middle Ages. The country saw significant contributions to Carolingian art, Ottonian art, and Norman art, as well as the flourishing of Byzantine art in cities such as Ravenna.

Italy was the main centre of artistic innovation during the Italian Renaissance (c. 1300–1600), beginning with the Proto-Renaissance of Giotto and culminating in the High Renaissance with artists such as Leonardo da Vinci, Michelangelo, Raphael, and Antonello da Messina. These artists influenced the development of Mannerism, the next phase of Renaissance art. Italy retained its artistic prominence into the 17th century during the Baroque period (c. 1600–1750) and into the 18th century with the emergence of Neoclassicism (c. 1750–1850). Both movements originated in Rome[4][5] and spread throughout Western art.

From the mid-19th century onward, Italy maintained a presence in the international art scene through movements such as the Macchiaioli, Futurism, Metaphysical art, Novecento Italiano, Spatialism, Arte Povera, and Transavantgarde.

Italian art has profoundly influenced many major artistic movements across the centuries and has produced numerous renowned painters, sculptors, and architects. Today, Italy continues to play a vital role in the global art scene, with major galleries, museums, and exhibitions. Key artistic centres include Rome, Florence, Venice, Milan, Turin, Genoa, Naples, Palermo, Syracuse and other cities. Italy is home to 60 World Heritage Sites, the highest number of any country in the world.

Etruscan art

[edit]

Etruscan bronze figures and terracotta funerary reliefs exemplify a vigorous Central Italian artistic tradition that declined by the time Rome began expanding its dominance over the peninsula.

The Etruscan paintings that have survived into modern times are predominantly wall frescoes found in tombs, especially in the necropolises of Tarquinia. These works represent the most significant examples of pre-Roman figurative art in Italy known to scholars.

Etruscan frescoes were painted onto wet plaster—a technique known as fresco—which allowed the pigments to bond with the plaster as it dried, thereby enhancing their durability. In fact, nearly all surviving Etruscan and Roman paintings are in this medium. The colours were made by grinding stones and minerals into pigments and mixing them with a binding medium. Fine brushes, often made from ox hair, were used to apply the paint.

From the mid-4th century BC onward, Etruscan artists began employing chiaroscuro techniques to suggest depth and volume. While some frescoes depict scenes of daily life, mythological themes are more common. Notably, Etruscan frescoes generally lack accurate anatomical proportion, and figures often display exaggerated or stylized features.

One of the most famous examples of Etruscan painting is the Tomb of the Lioness in Tarquinia.

Roman art

[edit]

The Etruscans were responsible for constructing some of Rome's earliest monumental buildings, and Roman temples and houses were initially modeled closely on Etruscan prototypes. Etruscan influence is evident in Roman temples, particularly in the use of a raised podium and the strong emphasis on the front façade over the remaining three sides. Similarly, large Etruscan houses were organized around a central hall, a layout later adopted in Roman domestic architecture as the atrium house.

Etruscan architectural influence gradually declined during the Roman Republic, as Rome increasingly absorbed elements from the broader Mediterranean world, especially Greek architecture. Since Etruscan architecture was itself influenced by the Greeks, the Roman adoption of Hellenistic styles was not an abrupt cultural shift. From the 3rd century BC onward, especially after the Roman conquest of Syracuse in 211 BC, a significant influx of Greek artworks and craftsmen entered Rome, exerting a decisive influence on Roman architectural development. By the time Vitruvius composed his architectural treatise De Architectura in the 1st century BC, Greek architectural theory and models had become dominant.

As the Roman Empire expanded, Roman architectural styles spread widely and were used for both public structures and, in wealthier cases, private residences. While local tastes influenced decorative details, the overall style remained distinctly Roman. In many regions, Roman and indigenous architectural elements coexisted within individual buildings, reflecting a syncretic vernacular tradition.

By the 1st century AD, Rome had become the largest and most advanced city in the world. The Romans developed innovative technologies to improve urban infrastructure, including sanitation, transportation, and construction. They engineered extensive aqueduct systems to supply the city with freshwater and constructed sewers to manage waste. While the wealthiest Romans resided in large, gardened villas, the majority of the population lived in multi-story apartment blocks made from stone, concrete, and brick.

Roman engineers discovered that mixing volcanic ash from Pozzuoli (near Naples) with lime and water produced an exceptionally durable form of cement. This allowed them to develop robust concrete structures, including large apartment buildings known as insulae.

Wealthy homes were often decorated with elaborate wall paintings depicting garden landscapes, mythological or historical narratives, and scenes of daily life. Floors were adorned with intricate mosaics composed of small, colored tiles arranged into decorative patterns or figural imagery. These artworks not only enhanced the brightness and apparent spaciousness of rooms but also served to display the owner's social status and cultural sophistication.[6]

In the Christian period of the late Empire (c. 350–500 AD), wall painting, floor and ceiling mosaics, and funerary sculpture continued to flourish, while free-standing sculpture and panel painting declined—likely due to changing religious sensibilities.[7] After Constantine the Great moved the imperial capital to Byzantium (renamed Constantinople), Roman art absorbed Eastern influences, giving rise to the Byzantine style. Following the sack of Rome in the 5th century, many artisans relocated to the Eastern capital. Under Emperor Justinian I, Roman artistic traditions reached a final, monumental expression with the construction of the Hagia Sophia and the creation of the famed mosaics of Ravenna, which employed thousands of craftsmen.[8]

Medieval art

[edit]

Throughout the Middle Ages, Italian art primarily took the form of architectural decoration, especially frescoes and mosaics. Byzantine art in Italy was characterized by a highly formalized and refined aesthetic, marked by standardized iconography, stylized figures, and the lavish use of gold and vivid color.

Until the 13th century, Italian art remained largely regional in character, shaped by a combination of local traditions and influences from both Western Europe and the Eastern Mediterranean. Around 1250, however, artistic developments across different Italian regions began to exhibit shared characteristics, leading to a growing sense of unity and the emergence of distinctively original styles.

Italo-Byzantine art

[edit]Following the fall of the Western Roman Empire, the Eastern Roman Empire—later known as the Byzantine Empire—continued to thrive for nearly a thousand years, with its capital at Constantinople.[9] Byzantine artisans were frequently employed on major artistic projects throughout Italy, and the influence of Byzantine aesthetics led to the development of the Italo-Byzantine style, which persisted in various forms into the 14th century.

The Italo-Byzantine style typically refers to religious paintings that imitate standard Byzantine iconography but were executed by Italian artists without formal training in Byzantine techniques. These works often feature subjects such as the Madonna and Child, rendered on gold ground panels. They introduced the format of small, portable framed paintings to Western Europe and played a central role in the devotional practices of the period.

This style dominated Italian painting until the late 13th century, when artists like Cimabue and Giotto began to forge a more naturalistic and emotionally expressive approach, particularly in Florence. Nevertheless, Italo-Byzantine painting continued to be produced in some regions and religious contexts well into the 15th century and beyond.[10]

Duecento

[edit]

Duecento is the Italian term referring to the 13th century, a formative period in Italian cultural and artistic history. During this time, Gothic architecture, which had originated in northern Europe, began to spread into Italy, particularly in the northern regions. However, Italian Gothic developed distinctive local variations, often more restrained and less vertically ambitious than its northern counterparts.

Two major religious orders—the Dominicans, founded by Saint Dominic, and the Franciscans, founded by Francis of Assisi—gained widespread popularity and financial support in this period. These mendicant orders undertook extensive church-building projects, often adopting simplified versions of Gothic architecture suited to their preaching missions and vows of poverty.

The use of large-scale fresco cycles became widespread during the Duecento, as frescoes were both cost-effective and useful for conveying religious narratives to largely illiterate congregations. A landmark example is the Basilica of Saint Francis of Assisi, a complex structure comprising two superimposed churches built on a hillside and begun shortly after Francis's canonization in 1228. The basilica was adorned with frescoes by many of the leading painters of the period, including Cimabue, Giotto, Simone Martini, Pietro Lorenzetti, and possibly Pietro Cavallini.

These artistic developments laid the groundwork for the innovations of the Trecento and the later Italian Renaissance.

Trecento

[edit]

Trecento is the Italian term referring to the 14th century, a pivotal period in the development of Italian culture and art. It is often regarded as the beginning of the Italian Renaissance, or more specifically, the Proto-Renaissance, a transitional phase that laid the groundwork for the innovations of the 15th century.

The most significant painter of the Trecento was Giotto di Bondone, whose work marked a decisive break from the stylized forms of the Italo-Byzantine tradition, introducing greater naturalism, expressive emotion, and a sense of three-dimensional space.

The Sienese School of painting also flourished during this period and was arguably the most prominent artistic center in Italy in the 14th century. Key figures included Duccio di Buoninsegna, whose Maestà is a landmark of early Italian panel painting; Simone Martini, known for his refined Gothic elegance; Lippo Memmi; and the brothers Ambrogio and Pietro Lorenzetti, who expanded narrative complexity and spatial experimentation in fresco.

In sculpture, notable artists included Arnolfo di Cambio and Tino di Camaino, both pupils of Giovanni Pisano, as well as Bonino da Campione.

Renaissance art

[edit]During the Middle Ages, painters and sculptors sought to convey a spiritual quality in their work. Artistic emphasis was placed on religious symbolism and conveying the sacred nature of Christian subjects, often at the expense of realistic representation. The goal was to inspire devotion and elevate the viewer’s thoughts toward the divine.

In contrast, Renaissance painters and sculptors, much like Renaissance writers, aimed to depict people and nature with greater realism. Influenced by the study of classical antiquity, they embraced observation, proportion, anatomy, and perspective to create more lifelike and emotionally resonant works. Figures were rendered with naturalistic detail and individuality, and compositions often incorporated settings inspired by real landscapes or classical architecture.

While medieval architects designed towering cathedrals to evoke the majesty of God and the humility of humanity, Renaissance architects turned to classical Roman models, emphasizing harmony, balance, and human-scale proportions. Buildings were designed according to mathematical ratios derived from the human body, as exemplified in the writings of Vitruvius and in works like Leon Battista Alberti’s De re aedificatoria. Ornamentation drew heavily from ancient Roman motifs such as columns, pilasters, friezes, and domes.

Early Renaissance

[edit]

During the early 14th century, the Florentine painter Giotto di Bondone became the first artist since antiquity to depict nature and the human form in a convincingly realistic manner. He produced influential frescoes for churches in Assisi, Florence, Padua, and Rome. Giotto sought to render figures with a sense of physical presence and emotional expression, placing them in spatially coherent and naturalistic settings.

A remarkable group of Florentine artists—including the painter Masaccio, the sculptor Donatello, and the architect Filippo Brunelleschi—emerged in the early 15th century, laying the foundations of the High Renaissance.

Masaccio's finest work is a series of frescoes painted around 1427 in the Brancacci Chapel of the Church of Santa Maria del Carmine in Florence. These frescoes depict Biblical scenes with dramatic realism and emotional gravity. Masaccio was among the first to apply Brunelleschi's recently developed system of linear perspective, allowing for more convincing spatial depth in painting.

Donatello revolutionized sculpture by reintroducing the classical ideals of the human form and individual expression. His works display a remarkable attention to anatomy and psychological depth. Among his most celebrated pieces is the bronze statue of David, completed in the 1430s. Standing approximately 5 feet (1.5 meters) tall, it is notable as the first life-sized, free-standing nude statue created in Western art since antiquity.

Brunelleschi was the first major Renaissance architect to systematically revive the forms and principles of ancient Roman architecture. He incorporated classical elements such as arches, columns, and harmonious proportions into his designs. One of his finest achievements is the Pazzi Chapel in Florence, begun in 1442 and completed around 1465, which exemplifies clarity, balance, and classical restraint. Brunelleschi also pioneered the use of linear perspective, a mathematical method for rendering three-dimensional space on a flat surface.

High Renaissance

[edit]

The arts of the late 15th century and early 16th century were dominated by three extraordinary figures: Leonardo da Vinci, Michelangelo, and Raphael.

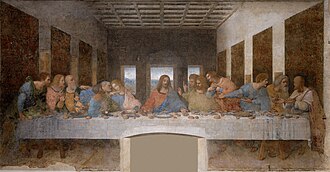

Leonardo da Vinci produced two of the most iconic works of Renaissance art: the wall painting The Last Supper and the portrait Mona Lisa. Leonardo was renowned not only for his art but also for his insatiable curiosity and scientific exploration. He meticulously studied the human body, producing detailed anatomical drawings, and he created thousands of pages of sketches and notes in which he documented his observations of nature, machines, and the human form. Leonardo's deep intellectual engagement with the world made him the quintessential Renaissance man and a symbol of the era's spirit of learning and discovery.[11]

Michelangelo was a master of many disciplines: painting, sculpture, architecture, and poetry. Widely regarded as one of the greatest sculptors in history,[12] Michelangelo's skill in portraying the human body is exemplified in his sculptures, such as the iconic statue of David (1501–1504), which conveys both physical beauty and intense psychological depth. He also painted the Sistine Chapel ceiling between 1508 and 1512, creating one of the most celebrated masterpieces of Western art. These frescoes depict Biblical and classical subjects and are renowned for their powerful representation of the human form and spiritual intensity.

Raphael's paintings are known for their harmonious composition, soft outlines, and graceful use of color. He was a master of perspective and proportion and is particularly famous for his Madonnas and portraits. One of his greatest works is the fresco The School of Athens, a grand depiction of classical Greek philosophers and scientists. The work reflects Raphael's admiration for classical antiquity, blending elements of ancient Greek and Roman art with the intellectual climate of the Renaissance.

The architect Donato Bramante is often regarded as the creator of High Renaissance architecture. In 1499, he moved to Rome, where he began his work with the design of the Tempietto (1502), a small, centralized dome structure that draws inspiration from Classical temple architecture. Pope Julius II appointed Bramante as the papal architect, and together they devised a plan to replace the 4th-century Old St. Peter's Basilica with a new, grand church. Though Bramante's vision was not completed in his lifetime, his designs had a profound influence on the development of Renaissance architecture.

Mannerism

[edit]

Mannerism was an elegant, courtly style that emerged in the later stages of the Italian Renaissance. It flourished particularly in Florence, Italy, where prominent figures such as Giorgio Vasari and Agnolo Bronzino were key representatives. The style was later introduced to the French court by Rosso Fiorentino and Francesco Primaticcio. The Venetian painter Tintoretto was also influenced by Mannerism.

Mannerism's characteristic approach to painting, with elongated figures, exaggerated poses, and artificial compositions, influenced other art forms as well. In architecture, Giulio Romano is one of the most notable examples of Mannerist influence. The Italian sculptor Benvenuto Cellini and the Flemish-born Giambologna were central figures in Mannerist sculpture, known for their dynamic and often exaggerated forms.[13]

Some historians view Mannerism as a decline or distortion of High Renaissance classicism, while others consider it an independent, complete style in its own right. The period is generally dated from around 1520 to 1600, often seen as an intermediary between the High Renaissance and the Baroque era.

Baroque and Rococo art

[edit]

In the early 17th century, Rome became the center of a revival of Italian dominance in the arts. In Parma, Antonio da Correggio decorated church vaults with lively figures floating softly on clouds—an approach that would profoundly influence Baroque ceiling paintings. The dramatic chiaroscuro paintings of Caravaggio and the robust, illusionistic works of the Bolognese Carracci family marked the beginning of the Baroque period in Italian art. Domenichino, Francesco Albani, and later Andrea Sacchi were among those who explored the classical implications of the Carracci's influence.

On the other hand, artists such as Guido Reni, Guercino, Orazio Gentileschi, Giovanni Lanfranco, and later Pietro da Cortona and Andrea Pozzo, though grounded in classical and allegorical traditions, initially painted dynamic compositions filled with gesticulating figures in a manner reminiscent of Caravaggio's style. The towering virtuoso of Baroque exuberance and grandeur in both sculpture and architecture was Gian Lorenzo Bernini. By around 1640, many painters began gravitating towards the classical style promoted by the French expatriate Nicolas Poussin in Rome. Sculptors like Alessandro Algardi and François Duquesnoy also aligned themselves with the classical ideals.

Notable late Baroque artists include the Genoese Giovanni Battista Gaulli and Neapolitans Luca Giordano and Francesco Solimena.

The leading figures of the 18th century hailed from Venice. Among them were the brilliant exponent of the Rococo style, Giovanni Battista Tiepolo; architectural painters such as Francesco Guardi, Canaletto, Giovanni Battista Piazzetta, and Bernardo Bellotto; and the engraver of Roman antiquities, Giovanni Battista Piranesi.

Neoclassical and 19th-century art

[edit]

Italian Neoclassicism was the earliest manifestation of the broader Neoclassicism movement and lasted longer than its counterparts in other European nations. It developed in opposition to the Baroque style around c. 1750 and persisted until c. 1850. The movement emerged during the rediscovery of Pompeii and spread throughout Europe as a generation of art students returned from their Grand Tour in Italy, influenced by the revived Greco-Roman ideals.

Like other European variants, Italian Neoclassical art was primarily based on the principles of Ancient Roman and Ancient Greek art and architecture. However, it also drew on the Italian Renaissance architecture and its foundational ideas, as seen in works like the Villa Capra "La Rotonda".[14] Classicism and Neoclassicism in Italian art and architecture also have deep roots in the Italian Renaissance, notably in the writings and designs of Leon Battista Alberti and the work of Filippo Brunelleschi.

Neoclassical art emphasized symmetry, proportion, geometry, and the regularity of parts, inspired by the architecture of Classical antiquity, particularly Ancient Rome. Key architectural elements included orderly arrangements of columns, pilasters, lintels, as well as the use of semicircular arches, hemispherical domes, niches, and aedicules. These replaced the more complex proportional systems and irregular profiles of medieval buildings. This style quickly spread across Italy and later to the rest of continental Europe.

Neoclassicism initially centered in Rome, where artists like Antonio Canova and Jacques-Louis David were active during the second half of the 18th century, before the movement spread to Paris. Painters of Vedute, such as Canaletto and Giovanni Paolo Panini, enjoyed significant success during the Grand Tour. The sculptor Antonio Canova became a leading exponent of the Neoclassical style, achieving international fame and being regarded as the most brilliant sculptor of his time.[15] Francesco Hayez is considered the foremost Italian exponent of Romanticism, with many of his works, often set in medieval contexts, containing encrypted patriotic messages related to the Risorgimento. Neoclassicism was the last Italian-born style, following the Renaissance and Baroque, to spread across all of Western art.

The Macchiaioli

[edit]

Italy produced its own form of Impressionism, known as the Macchiaioli movement, which preceded the more famous Impressionist artists in France. Key figures of the movement included Giovanni Fattori, Silvestro Lega, Telemaco Signorini, and Giuseppe Abbati. The Macchiaioli artists are considered forerunners to Impressionism, as they emphasized the importance of light and shadow, or macchie (literally "patches" or "spots"), as the central elements of their works. The term macchia was commonly used by 19th-century Italian artists and critics to describe the vibrant, sketchy, and spontaneous quality in a painting or drawing, or to highlight the harmonious, broad effect in a composition.

A hostile review published on 3 November 1862, in the journal Gazzetta del Popolo, marks the first recorded use of the term Macchiaioli.[16] The term carried several connotations: it mockingly suggested that the artists' finished works were no more than sketches, and also alluded to the phrase "darsi alla macchia," which idiomatically meant to "hide in the bushes or scrubland." The artists often worked outdoors in such environments, which contributed to this association. Furthermore, the name implied that the Macchiaioli were outlaws, reflecting the traditionalists' view that these new artists were working outside the established rules and conventions of the art world at the time.

Italian modern and contemporary art

[edit]

In the early 20th century, exponents of Futurism developed a dynamic vision of the modern world, while Giorgio de Chirico expressed a strange metaphysical quietude. Amedeo Modigliani became associated with the School of Paris. Notable later modern Italian artists include the sculptors Giacomo Manzù and Marino Marini, the still-life painter Giorgio Morandi, and the iconoclastic painter Lucio Fontana. In the second half of the 20th century, Italian designers, particularly those based in Milan, profoundly influenced international styles with their imaginative and functional works.

Futurism

[edit]

Futurism was an Italian art movement that flourished from 1909 to around 1916. It was the first of many art movements that sought to break with the past in all areas of life. Futurism glorified the power, speed, and excitement characteristic of the machine age. The Futurists learned from French Cubist painters and multiple-exposure photography to break up realistic forms into multiple images and overlapping fragments of color. By such means, they sought to portray the energy and speed of modern life. In literature, Futurism demanded the abolition of traditional sentence structures and verse forms.[18]

Futurism was first announced on 20 February 1909 when the Paris newspaper Le Figaro published a manifesto by the Italian poet and editor Filippo Tommaso Marinetti. (See the Manifesto of Futurism.) Marinetti coined the word "Futurism" to reflect his goal of discarding the art of the past and celebrating change, originality, and innovation in culture and society. His manifesto glorified the new technology of the automobile and the beauty of its speed, power, and movement. Exalting violence and conflict, Marinetti called for the sweeping repudiation of traditional values and the destruction of cultural institutions such as museums and libraries. The manifesto's rhetoric was passionately bombastic, and its aggressive tone was deliberately intended to inspire public anger and arouse controversy.

Marinetti's manifesto inspired a group of young painters in Milan to apply Futurist ideas to the visual arts. Umberto Boccioni, Carlo Carrà, Luigi Russolo, Giacomo Balla, and Gino Severini published several manifestos on painting in 1910. Like Marinetti, they glorified originality and expressed disdain for inherited artistic traditions.

Boccioni also became interested in sculpture, publishing a manifesto on the subject in the spring of 1912. He is considered to have most fully realized his theories in two sculptures: Development of a Bottle in Space (1912), in which he represented both the inner and outer contours of a bottle, and Unique Forms of Continuity in Space (1913), in which a human figure is not portrayed as one solid form but is instead composed of multiple planes that represent the space through which the figure moves.

Futurist principles extended to architecture as well. Antonio Sant'Elia formulated a Futurist manifesto on architecture in 1914. His visionary drawings of highly mechanized cities and boldly modern skyscrapers prefigure some of the most imaginative architectural planning of the 20th century.

Boccioni, who had been the most talented artist in the group,[19] and Sant'Elia both died during military service in 1916. Boccioni's death, combined with the expansion of the group's personnel and the sobering realities of the devastation caused by World War I, effectively brought an end to Futurism as an important historical force in the visual arts.

Metaphysical art

[edit]Metaphysical painting is an Italian art movement that originated in 1917 with the work of Carlo Carrà and Giorgio de Chirico in Ferrara. The term "metaphysical," adopted by De Chirico himself, is central to the poetics of the movement.

The movement is characterized by dreamlike imagery, with figures and objects seemingly frozen in time. Artists associated with Metaphysical painting embraced the representation of the visible world through traditional perspective, but with an unusual arrangement of human figures, which often appear as lifeless models, and objects placed in strange, illogical contexts. These works are marked by unreal lighting, unnatural color schemes, and the stillness of figures that contribute to a sense of eerie timelessness.

Novecento Italiano

[edit]

The Novecento movement was a group of Italian artists formed in 1922 in Milan, advocating for a return to the great Italian representational art of the past.

The founding members of the Novecento movement (Italian: "20th-century") were the critic Margherita Sarfatti and seven artists: Anselmo Bucci, Leonardo Dudreville, Achille Funi, Gian Emilio Malerba, Piero Marussig, Ubaldo Oppi, and Mario Sironi. Under Sarfatti's leadership, the group sought to renew Italian art by rejecting European avant-garde movements and embracing Italy's artistic traditions.

Other artists associated with the Novecento movement included sculptors Marino Marini and Arturo Martini, and painters Ottone Rosai, Massimo Campigli, Carlo Carrà, and Felice Casorati.

Spatialism

[edit]Spatialism was a movement founded by the Italian artist Lucio Fontana, with its principles expressed in manifestos between 1947 and 1954.

Combining elements of concrete art, Dada, and Tachism, the movement's adherents rejected traditional easel painting and embraced new technological developments, seeking to incorporate time and movement into their works. Fontana's slashed and pierced paintings exemplify his ideas.

Arte Povera

[edit]| Part of a series on the |

| Culture of Italy |

|---|

|

| People |

| Traditions |

Arte Povera is an artistic movement that originated in Italy in the 1960s, combining elements of conceptual, minimalist, and performance art. The movement made use of everyday, often discarded materials, such as earth and newspaper, with the aim of subverting the commercialization of art. The phrase "Arte Povera" is Italian and literally translates to "impoverished art."

Transavantgarde

[edit]The term Transavantgarde was coined by the Italian critic Achille Bonito Oliva. He defined Transavantgarde art as traditional in format (mainly painting or sculpture), apolitical, and, above all, eclectic.

List of major museums and galleries in Italy

[edit]Advocacy and restrictions

[edit]According to the 2017 amendments to the Italian Codice dei beni culturali e del paesaggio[20][21], a work of art can be legally defined as being of public and cultural interest if it was completed at least 70 years ago. The previous limit was 50 years. To facilitate the export and international trade of art as a store of value, private owners and their dealers were granted the ability to self-certify a commercial value below €13,500, enabling them to transport goods across the country’s borders and into the European Union without needing public administrative permission for such transactions.[22][23]

The bill was passed and came into force on 29 August 2017.[21] Public authorization is required for archaeological remains discovered underground or underwater.[20]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "The Theft That Made Mona Lisa a Masterpiece". All Things Considered. 30 July 2011. NPR. Retrieved 15 February 2019.

- ^ Sassoon, Donald (21 September 2001). "Why I think Mona Lisa became an icon". Times Higher Education.

- ^ Carrier, David (2006). Museum Skepticism: A History of the Display of Art in Public Galleries. Duke University Press. p. 35. ISBN 978-0-8223-3694-5.

- ^ Stevenson, Angus (19 August 2010). Oxford Dictionary of English. OUP Oxford. ISBN 978-0-19-957112-3.

- ^ "The road from Rome to Paris. The birth of a modern Neoclassicism". Archived from the original on 14 July 2015. Retrieved 5 January 2016.

- ^ Alex T. Nice, Ph.D., former Visiting Associate Professor of Classics, Classical Studies Program, Willamette University. Nice, Alex T. "Rome, Ancient." World Book Advanced. World Book, 2011. Web. 30 September 2011.

- ^ Piper, p. 261.

- ^ Piper, p. 266.

- ^ [1] Archived 17 August 2011 at the Wayback Machine Byzantium. Fordham University. Accessed 6 October 2011.

- ^ Drandaki, Anastasia, "A Maniera Greca: content, context and transformation of a term," Studies in Iconography, vol. 35, 2014, pp. 39–41, 48–51.

- ^ James Hankins, Ph.D., Professor of History, Harvard University.

Hankins, James. "Renaissance." World Book Advanced. World Book, 2011. Web. 1 October 2011. - ^ Pope-Hennessy, John Wyndham. Italian High Renaissance and Baroque sculpture. Phaidon Press, 1996. p. 13. Web. 5 October 2011.

"Michelangelo was the first artist in history to be recognized by his contemporaries as a genius in our modern sense. Canonized before his death, he has remained magnificent, formidable, and remote. Some of the impediments to establishing close contact with his mind are inherent in his own uncompromising character; he was the greatest sculptor who ever lived, and the greatest sculptor is not necessarily the most approachable." - ^ Eric M. Zafran, Ph.D., Curator, Department of European Paintings and Sculpture, Wadsworth Atheneum.

Zafran, Eric M. "Mannerism." World Book Advanced. World Book, 2011. Web. 1 October 2011. - ^ "Villa Almerico Capra detta "la Rotonda", Vicenza" (in Italian). Retrieved 30 December 2023.

- ^ Rosenblum, Robert; Janson, Horst Woldemar. 19th century art. Archived 27 October 2022 at the Wayback Machine Abrams, 1984. p. 104. Web. 5 October 2011.

"Antonio Canova (1757–1822) was not only the greatest sculptor of his generation; he was the most famous artist of the Western world from the 1790s until long after his death." - ^ Broude, p. 96.

- ^ "Women in Art, PDF" (PDF). shareholder.com. Retrieved 7 September 2018.[dead link]

- ^ Douglas K. S. Hyland, Ph.D., Director, San Antonio Museum of Art.

Hyland, Douglas K. S. "Futurism." World Book Advanced. World Book, 2011. Web. 4 October 2011. - ^ Wilder, Jesse Bryant. Art History for Dummies. John Wiley & Sons, 2007. p. 310. Web. 6 October 2011.

- ^ a b "Codice dei beni culturali e del paesaggio". Chamber of Deputies (Italy) (in Italian). Archived from the original on 20 November 2019. Retrieved 14 September 2020.

- ^ a b "LEGGE 4 agosto 2017, n. 124". Gazzetta Ufficiale (in Italian). at article n. 175.

- ^ "L'Appello a Mattarella – "I beni culturali non sono commerciali: presidente non firmi il Dl Concorrenza"". Il Fatto Quotidiano (in Italian). 4 August 2017.

- ^ "Shorthand account of the Parliamentary session held on June 28, 2017". Chamber of Deputies (Italy) (in Italian).

External links

[edit]- Artworks by the main Italian artists

- [2] Italian Art. kdfineart-italia.com. Web. 5 October 2011.

- [3] Archived 15 June 2020 at the Wayback Machine Italian and Tuscan style Fine Art. italianartstudio.com. Web. 5 October 2011.

- [4] Italian art notes